Intro

I have been using F# for a year and a half or so now for all sorts of things - general tools, scripts and utilities for work, XNA games / graphics / AI simulations, some async layers for rx-driven silverlight applications and so forth. I'm still pretty new to the functional paradigm, which I have been embracing (with a great deal of mind melting, and destruction of my OOP and procedural shackles). One thing I struggled with initially was the subject of function composition, and its relationship to partial function application and so forth. I understood the theory behind it but couldn't really see WHY I would want to use it.

Recently I have been learning a bit of Haskell, using the excellent book Haskell : The Craft of Functional Programming. This really helped switch a lot of lights on with regards to functional programming, introducing function composition in chapter 1. The books follows a theme of building a simple "Picture" manipulation library based upon function composition, partial application and so forth. I thought it would be cool to covert these into F# and also have a crack at the various exercises presented in the book, and it has been fun. I share this experience with you in the hopes that some other novice functional programmers might have some "light switched on!" moments when thinking about functional techniques.

It is assumed the reader will have a working knowledge of the F# language including all the basic syntax, data types, pattern matching, lambda expressions and pipelining. You already know why functional programming is cool and the benefits it offers, but are a bit mystified with how to apply these seemingly complex functional techniques. If you are a C# developer making the move to F# then you will want to go and learn all the basics of the language first, otherwise you are probably not going to be able to follow this all that well.

Setting the Scene!

Our representation of a "picture" is simply a 2-dimensional list of characters, where each character may be '.' or '#'. In F# this is simply defined as char list list

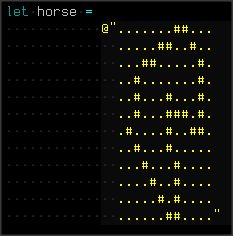

An example of a suitable picture is shown here, in a string format which is much easier to represent in the script file than a whole bunch of character lists:

Granted, it looks bugger all like a horse, but you can blame the Haskell book for that ;) We create a simple function that will parse this string, dumping whitespace found in the source file, and then converting each line into a list of characters

let pictureOfString (input:string) =

input.Split([|'\n'|], StringSplitOptions.RemoveEmptyEntries)

|> List.ofArray

|> List.map( fun s -> s.Trim().ToCharArray() |> List.ofArray)

And another little function for showing printing the results

let printPicture picture =

let printer line =

line |> List.iter( printf "%c" )

printfn ""

picture |> List.iter printer

Here the inner function printer has inferred the argument line to have a type of char list. This is because we have applied the line argument to a list processing higher-order function List.iter, so the type inference knows that line must be a list of some description, and we have then used printf "%c" on each item of the list. The "%c" notation tells printf to look for a char and thus the type of line must be char list. Notice we have not explicitly applied the printfn function to each character, this has been done automatically for us by the List.iter function. We will see why this works later. We could have equally written line |> List.iter( fun c -> printf "c%" c ). Similarly, the argument picture is inferred to have type char list list because we have used List.iter and applied our printer function to it, once again allowing the argument to be automatically applied to the printer function without explicitly applying it.

With that being done, it is now possible to start writing some functions that will perform some processing on the picture. A desirable function would be one that takes an input picture, flips it along the horizontal plane, and returns a new picture object. We can think of this mirror flip simply as reversing the order of the outer lines. Therefore we can create this function as a direct alias to the List.rev library function.

let flipH = List.rev

So, nothing too amazing has happened here. We have aliased the inbuilt library function that reverses the given list, and this will produce the behaviour we expect when we put it to the test.

horse

|> pictureOfString

|> flipH

|> printPicture

Now, for something slightly more interesting. We wish to write a function that will flip a picture on the vertical plane. This is a similar operation to the previous one, except it is apparent that the contents of each line needs to be reversed. That is, rather than reversing the whole list of lines, instead we wish to transform each line in the list with a reverse operation. When thought about in this way, it should become apparent that the function List.map is appropriate, as it is designed to call some function on each entity of a given list and create a new list from the results (this is called Select in LINQ). The function we pass into map must be compatible with the type it will be operating on, and since our inner type is another list, we can use any function that takes a list as an input. The function we wish to use in the map command is simply List.rev again which will reverse each inner list, so that

let flipV = List.map (fun x -> List.rev x)

or

let flipV = List.map List.rev

Note here that once again we have not applied this new function to any arguments, we have just defined a new function by layering two existing functions, so that ultimately we have a function that still accepts an arbitrary list of lists of any type and produces a new value of the same type as the input (because List.rev obviously returns the same type as it was given as an input). All that we have really done here is provided a definition that will feed the result of one function straight into another one. This is a form of function composition by way of using functions as first-class values and it works because List.map is a higher-order function. That is, a function that takes another function as a parameter and encapsulates executing some common pattern with that function. This is polymorphism in a functional language (or to be more precise, it is called parametric polymorphism which is the ability to write functions that execute identically regardless of data types). In the case of map it is executing the supplied function on each item of the input list and building a new list with the results. If you apply this function to lists with different types, you might notice that the type inference system has inferred the new function to have a type of 'a list list -> 'a list list and this is because the List.rev function takes a 'a list and so it has determined that the map function must accept a list of lists of 'a. Pretty clever!

The second version of the function above is written in what is called point-free style (which has something to do with topology in maths I think). Essentially this is the application of arguments to functions without explicitly using the arguments - and in this case we are automatically applying the argument that will be passed in from List.map to List.rev. We have already seen this style in the printPicture function. We shall prefer the point-free style in these articles as it is the more compact and succinct version (and it's more flash! However, it can decrease the readability of a function definition).

For the next function, we would like to be able to rotate the image. We can already accomplish this using our new functions defined above, as a rotation is the effect of applying a horizontal and vertical flip on an image. It is interesting to note that these functions can be applied in either order to exactly the same effect. In order to achieve this we could write the function in a variety of ways, including writing an explicitly defined function that take an input and then pipes or applies it into the two functions like so

let rotate a = a |> flipH |> flipV

or

let rotate a = flipV (flipH a)

However, F# already has operators built in that do exactly the above in a more concise manner, and the ability to compose functions together with an operator can be a powerful technique as we will hopefully see later on. There are two built in function composition operators, >> and <<, the forward and backward composition operator respectively. You can think of these as identical to |> and <| but without applying arguments to the resulting functions. This means you can replace a long pipeline of |> operators with >> operators if you remove the application of the argument to the first function in the pipeline.

Therefore, f >> g means "execute function f and call function g with its result" and the result of this is a new function that accepts whatever the input argument of function f was and results in whatever the output of function g was. Because the result of f is passed to x, a constraint obviously exists in that the input of g must be the same as the output of f. The backwards composition operator is the same thing but in reverse, so that g << f has the same meaning as f >> g

let rotate = flipH >> flipV

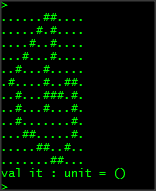

Let's test the new rotate function:

horse

|> pictureOfString

|> rotate

|> printPicture

The last two functions we will create in this article will deal with being able to create new pictures by taking two existing pictures and creating a new one out of them. One function will stack pictures vertically, and the other will put them alongside each other. First we will look at the stacking function as it is the easier of the two. Given two pictures, to stack them vertically, all we really need to do is append the two lists, which is easy! F# already has an operator for this, the @ operator. Therefore our definition to stack two pictures is simply this operator which we will alias onto our own function name:

let stack = (@)

Here we have wrapped the @ operator in parentheses. This tells the compiler that we want to use the @ operator as a function instead of an operator. Operators in F# are in fact just functions like everything else, the only difference being that you can apply arguments to the function by placing them on either side of the operator. Operators are sometimes called symbolic functions - that is, functions that use a symbol instead of a word, and you can define your own symbolic functions (which is awesome). This is different from the concept of operator overloading which you will be used to in an OOP language.

The second function seems to be more tricky. If you think about it though, all we need to do is take two lists, and for each line in each list, join them together and output one combined list at the end. You can visualise this like so:

List A List B

"........###...." @ "....####......."

"........###...." @ "....####......."

"........###...." @ "....####......."

Looking at the wonderful inbuilt functions in the List module, you will see there is a function called List.map2 which has the following type signature ('T1 -> 'T2 -> 'U) -> 'T1 list -> 'T2 list -> 'U list. These type signatures can be confusing to read at first, but you should learn how to read them well because they can yield a great deal of information about what the function probably does. Here the first parameter ('T1 -> 'T2 -> 'U) is a function that takes one element of type 'T1, another element of 'T2, performs some logic on them and results in a new value of type 'U. It then accepts two lists of type 'T1 and 'T2 and finally produces a list of 'U. This is exactly what we need to perform the side-by-side joining of our pictures. We can write this explicitly like so:

let sideBySide = List.map2( fun item1 item2 -> item1 @ item2 )

Because we have used the @ operator, the type inference system will know that the items in both lists must be a list of something, but it will not care what type those lists are. In fact, we can shorten this even further by using the point free style again here like so:

let sideBySide = List.map2 (@)

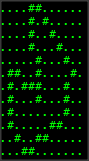

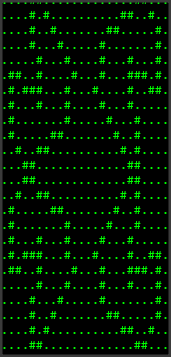

Which is much more elegant! Now let's some our functions together in a more complex pipeline. We will have to be slightly more careful now as the new stack and sideBySide functions will only work if the two input lists are of equal size.

horse

|> pictureOfString

|> fun pic -> sideBySide (rotate pic) pic

|> fun pic -> stack pic (flipH pic)

|> printPicture

What's going on here? The second part of the pipeline calls sideBySide which is expecting two parameters. Obviously the pipeline operator is only passing one argument. What I wanted to do is use the same picture created from pictureOfString, so to facilitate this I have used an anonymous function which captures the horse picture as the argument pic. I have then applied the unchanged pic as one argument to the sideBySide function, and I have called rotate on pic to produce the second argument to the sideBySide function. In the third stage of the pipeline I have done almost exactly the same thing, but using stack and flipH on the results of the previous stage of the pipeline.

Why does the "point free" style work?

In order to understand this, you must first understand that in F#, every function has only one argument. When you apply arguments to a function, F# simply applies the first one, returns a new function which accepts the remaining arguments, then applies the next argument, and so on. This is called partial function application and this can be used anywhere. It is totally valid syntax to apply only some arguments to a function, you will simply receive a few function in return which takes the remaining arguments. We can use this greatly to our advantage in many places.

If we return to the printPicture function, and look at the definition of the inner function printer. Here we have used printf but we have not applied all of the arguments to it. If you execute the command (printf "c%") in F# interactive, it will return a type of (char -> unit). What we have done here is partially applied the printf function with only its first argument, and it has returned us a new function that is expecting the remaining char argument and returns a unit (equivalent to void). Now if you look at the definition of List.iter you will see its type is ('T -> unit) -> 'T list -> unit. The first argument is expecting a function of type 'T -> unit which is exactly what our partially applied printf function has given us! Therefore, when the iteration function executes, at some point it is going to take the passed in function and apply it to an item in the list, which satisfies the rest of the partially applied printf function we have passed in. You can also see this directly at work in the way we call the printer function in the last line. I hope that makes sense, it is a little awkward to try and explain.

That's it for the first part of these articles, I hope it has helped show how the functional style can be very succinct and elegant. In the next part, we will create some more interesting functions for the picture library such as superimpose, invertColour, scale and also see how we can use the composition operators in a dynamic way to build up functions that compose themselves with themselves (!!)

If you are really serious about functional programming, I highly recommend you have a go at learning a pure functional language, it will greatly help with the way you design your F# programs.

Footnote: If any expert functional programmers are reading this, I might have messed up the definitions of some techniques, or got some stuff wrong. I'm far from being a master functional programmer, so go easy on me! :)

I have attached an F# script file containing the code covered :

Picture.fsx (1.25 kb)